Biofim basics – The Formation of Biofilm

A Brief History of “Biofilm”

Center for Biofilm Engineering

Montana State University

Microbial communities attached to surfaces (biofilms) were observed long before people had the tools to study them in detail. In 1684, Antony van Leeuwenhoek remarked on the vast accumulation of microorganisms in dental plaque in a report to the Royal Society of London: “The number of these animalcules in the scurf of a man’s teeth are so many that I believe they exceed the number of men in a kingdom.”

The study of microbes took an important turn in the mid-1800s when Robert Koch developed methods to create a solid nutrient medium to grow and isolate pure cultures of microorganisms. This development led to huge advances in medicine, agriculture, and industry. However, these advances were based on such a simplistic concept of microbial life that many of the ‘solutions’ generated by these techniques are now being reversed. Microorganisms have proved to be much more complex and less tractable than ever imagined.

In a 1940 issue of the Journal of Bacteriology, authors H. Heukelekian and A. Heller wrote, “Surfaces enable bacteria to develop in substrates otherwise too dilute for growth. Development takes place either as bacterial slime or colonial growth attached to surfaces.” Claude ZoBell described many of the fundamental characteristics of attached microbial communities in the 1940s. In the late decades of the 20th century, numerous articles were written about microbial films or slime layers; German researchers sometimes used the term “Schmutzdecke.” As the unique properties of microbial communities vs planktonic microbes grew more apparent, it became helpful to use a special term to describe them. “Biofilm” was used colloquially among researchers for some years before it was considered a term acceptable for use in publication. The earliest use of “biofilm” in publication is in the Swedish journal Vatten: Harremoës, P. 1977. “Half-order reactions in biofilm and filter kinetics,” Vatten, 33 122-143. (If you know of an earlier publication with “biofilm” in it, please let us know; we would be happy to make a correction.)

Early biofilm researchers studied the implications of biofilms in waste-water filtration, biofouling of industrial equipment, and dental plaque (Leeuwenhoek would have been pleased). Since bacteria preferentially attach to surfaces, biofilms are virtually ubiquitous. Biofilm formation is also implicated in microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC), product contamination, medical device-related infections, and chronic wounds. Biofilm can also be used for positive effects, especially in water pretreatment systems and contaminated soils.

In 1990, recognizing the significance of microbial activity, as well as the tremendous economic costs associated with microbial communities on surfaces, the US National Science Foundation founded the Center for Biofilm Engineering at Montana State University in Bozeman (though, interestingly, NSF would not initially accept the word “biofilm” in the Center’s name; instead the award funded the “Center for Interfacial Microbial Process Engineering”). Since that time, the field of biofilm research has exploded. New tools and techniques are continually pioneered to help understand the secrets of microbial community interactions. In addition to numerous research laboratories in the US, several groups study biofilms worldwide, including centers in Denmark, England, Germany, Australia, and Singapore.

Biofilm, what is it?

Most of you have never heard of the term “biofilm,” but you have undoubtedly encountered “biofilm” on a routine basis. If you’ve ever been to the dentist and he’s scraped “plaque,” which causes tooth decay, off your teeth, that’s a type of bacterial biofilm. The “slime” that clogs your drains is also biofilm. The slippery coating on rocks at the water’s edge of a stream or river is just bacterial biofilm-coating—Pond-scum – a biofilm. If you’ve ever been diagnosed with Candida albicans, H. pylori, chronic sinus or prostate infection, or Lyme disease, chances are they’re living, hiding, and replicating in a biofilm colony.

Iodine staining of biofilm plaque (upper right)

This is the best product for removing the bacterial biofilm that causes plaque – Biotene PBF Chewing Gum.

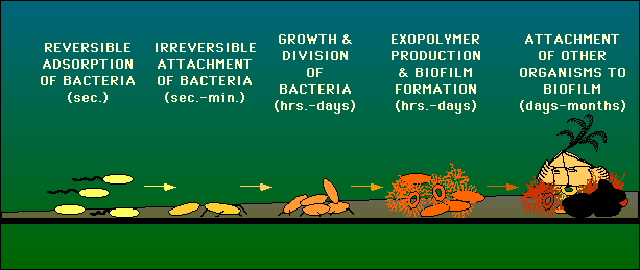

These microorganisms (biofilm colonies) are usually encased in an extracellular polysaccharide (*) that they synthesize via the release of signaling molecules through quorum sensing (QS). This glue-like substance allows them to anchor to various surfaces – such as metals, plastics, soil particles, medical implant materials such as pacemakers, and tissue. A bacterial biofilm can form anywhere as long as sufficient moisture and nutrients are available. In your body, that would be from your mouth, especially the teeth, through the stomach and GI tract, and down to the rectum. Biofilm in the environment can often be found in ponds, streams, rivers, etc. A single bacterial species can form biofilm, but more often than not, biofilms consist of many species of bacteria, as well as fungi/yeast, algae, protozoa, debris, and corrosion products. Once anchored to a surface, biofilm microorganisms carry out a variety of detrimental or beneficial reactions, depending on the surrounding environment or body conditions.

(*) Extracellular polymeric substances, or EPS, are the slimy material that bacteria excrete and surround themselves with as they form biofilms. EPS are mostly water (up to 95%), but the remaining ingredients include a complex mixture of lipids, saccharides (sugars), and bacterial debris such as cell fractions, DNA, and proteins.

In the human body, biofilm colonies are the main reason certain conditions take so long to handle. In my opinion, if it were not for “biofilm,” conditions caused by the microorganisms – Candida albicans, Candida spp, H. pylori, Lyme bacteria (Borrelia burgdorferi) and many others, would be far easier to diagnose and/or treat. It is crucial in any treatment protocol to first handle the biofilm. Doing so will make a significant difference in the amount of time, money, and effort spent on treating many so-called stubborn conditions – like the above.

Updated Definition and Current Relevance (March 2019)

Biofilms are a structured community of bacterial cells enclosed in a self-produced polymeric matrix and adherent to inert or living surfaces1. Forming a biofilm is a common trait of a diverse array of microbes, including lower-order eukaryotes, with biofilms being recognized as the dominant mode of bacterial growth1,2,3. Biofilms are the root cause of various chronic infections, such as lung infections in patients suffering from cystic fibrosis infections related to indwelling medical devices, such as ventilator-associated pneumonia in intubated patients, and urinary tract infections due to catheters1.

The National Institutes of Health estimated that 65% of all nosocomial infections are due to bacteria growing as biofilms and that biofilms are responsible for over 80% of microbial infections. Furthermore, the United States Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimated that biofilms are the etiologic agent in 60% of all chronic infections, including biofilms associated with cystic fibrosis (CF), burn wounds, and chronic wounds. Biofilm-related infections likely account for 1.7 million infections and 99,000 associated deaths, with over $7 billion spent annually on the treatment of nosocomial infections. The high infection and death toll has been attributed to the extraordinary resistance of biofilms to antimicrobial agents1,4,5, with biofilms having been reported to be up to 1000-fold less susceptible than their planktonic counterparts to various antibiotics6. In addition, biofilms have been reported to inhibit wound healing7,8,9. It is, thus, not surprising that biofilms have been reported to be refractory to conventional antibiotic treatment therapies1,4. For instance, while the development of antimicrobial burn creams was considered a significant advance in the care of wound patients10, infections of wounds remain the most common cause of morbidity and mortality among the 6.5 million people suffering from wounds in the United States alone, causing over 200,000 deaths annually11,12. The most affected are people suffering from burn wounds, for which almost 61% of deaths are caused by infection10,13. Treatment failure has been primarily attributed to the principal wound pathogens Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their ability to form biofilms in wounds1,4,5,10.

1. Costerton, J. W., Stewart, P. S. & Greenberg, E. P. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284, 1318–1322 (1999).

2. Geesey, G. G., Richardson, W. T., Yeomans, H. G., Irvin, R. T. & Costerton, J. W. Microscopic examination of natural sessile bacterial populations from an alpine stream. Can. J. Microbiol 23, 1733–1736 (1977).

3. Costerton, J. W. et al. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41, 435–464 (1987).

4. Lewis, K. Multidrug tolerance of biofilms and persister cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 322, 107–131 (2008).

5. Spoering, A. L. & Lewis, K. Biofilms and planktonic cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa have similar resistance to killing by antimicrobials. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6746–6751, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.183.23.6746-6751.2001 (2001).

6. Davies, D. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2, 114, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1008 (2003).

7. Seth, A. K. et al. Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm–infected wounds with clinical wound care strategies: a quantitative study using an in vivo rabbit ear model. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 129, 262e–274e (2012).

8. Seth, A. K. et al. Comparative analysis of single-species and polybacterial wound biofilms using a quantitative, in vivo, rabbit ear model. PLoS ONE 7, e42897 (2012).

9. Edwards, R. & Harding, K. G. Bacteria and wound healing. Current opinion in infectious diseases 17, 91–96 (2004).

10. Cancio L. C. et al. wound infections. In: Holzheimer, R. G., Mannick, J. A., editors. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt (2001).

11. Wolcott, R. et al. Chronic wounds and the medical biofilm paradigm. Journal of wound care 19, 45–46, 48–50, 52–43 (2010).

12. Sen, C. K. et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair and Regeneration 17, 763–771 (2009).

I have a chronic intense skin irritation recurring annually in late summer for many years. Dry bumps emerge on posterior arms bilaterally. Once erupted itching stops. It seems to travel the entire arm distance before it runs its course. Do spirochete bacteria produce this type of condition? What other pathogens might cause this to occur? I was diagnosed 4 years ago with H. pylori and took 2 rounds of antibiotics. Post antibiotic breath test was negative, no post antibiotic blood test was ordered.

Peggy,

Without seeing you it’s hard for me to give you specific advice. I highly doubt it’s a bacteria. I’ve seen it develop as a result of gluten sensitivity, lack of GLA (black currant, borage or evening primrose oil), B-complex deficiency (specifically choline), and a few other issues. Here is a link to what most people call, bumps on the back of the arms. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/bumps-and-growths/keratosis-pilaris

I hope this helps.

Respectfully,

Dr. Ettinger

If this condition is gluten related wouldn’t it be year round? This has occurred at the same time(August)every year and lasts about 8-10 weeks.

I’m wondering about Morgellon’s and/or a side effect of chronic Lyme disease. Does this sound plausible?

Peggy, you are correct it theoretically would be year round, just like if it were Morgellon’s or Lyme. It’s possible the heat or humidity could be a catalyst? It’s tough to tell w/o testing.