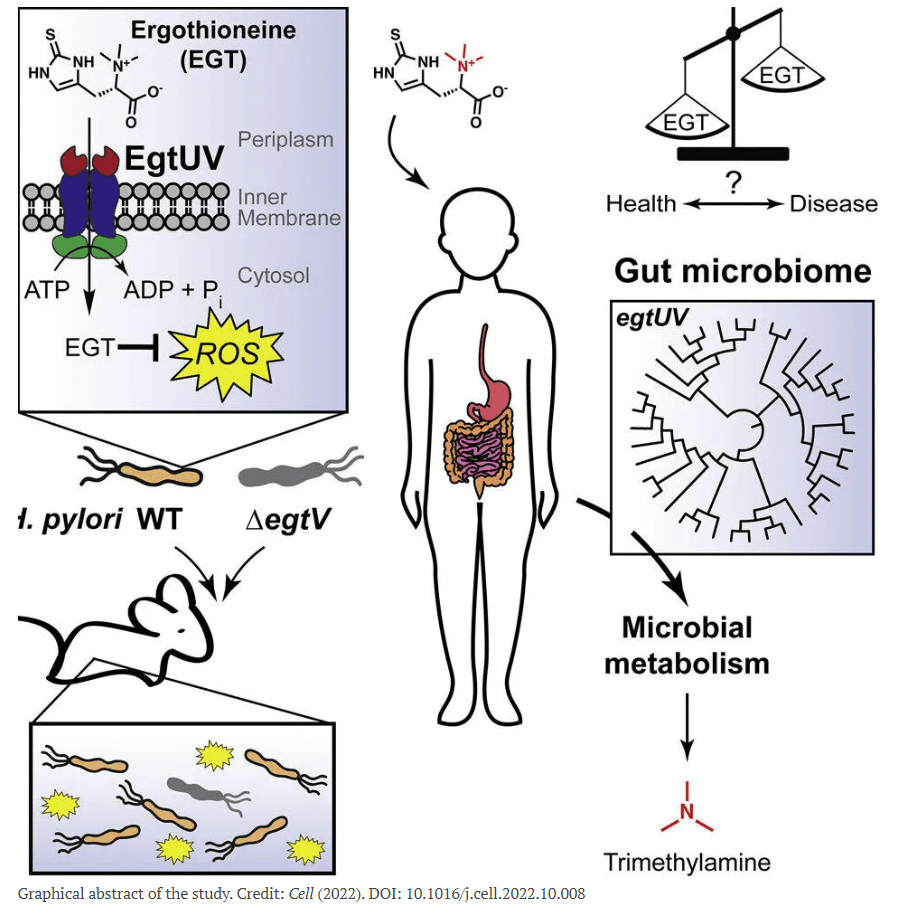

In a newly published Yale study, researchers have identified, an otherwise beneficial antioxidant compound, known as ergothioneine (EGT), may actually protect or selectively confer a competitive colonization advantage in host (stomach and duodenal) tissue, to the potentially pathogenic bacteria, H. pylori. Basically, ergothioneine may help H. pylori survive. This is okay if it’s minding its own business and there are no ulcer or gastritis symptoms, or there is no family history of stomach cancer. That said if you need to get rid of H. pylori, ergothioneine may just make its eradication more difficult.

Helicobacter pylori, or H. pylori, is a type of bacteria that can infect the lining of the stomach and duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). It is a common cause of peptic ulcers and can also contribute to the development of gastritis, which is inflammation of the stomach lining. H. pylori infection is typically diagnosed with a blood test, breath test, or stool test, and it can be treated with a combination of antibiotics, natural antimicrobials, and acid-blocking medications.

Ergothioneine is a naturally occurring amino acid that is found in small amounts in certain foods, including mushrooms, oats, grains, and beans. It is an antioxidant, which means that it can help protect cells of the body, such as skin cells, from damage caused by substances called free radicals.

In more detail, the nutrient, ergothioneine, is a thiol-containing antioxidant that can protect cells, like the skin, from oxidative stress*. A thiol is a type of sulfur-containing compound. It is a molecule that contains a functional group called a thiol group (-SH), which consists of a sulfur atom bonded to a hydrogen atom. Some amino acids, such as cysteine and homocysteine, contain thiol groups and are therefore classified as thiol-containing amino acids. These amino acids play important roles in various biological processes, including protein synthesis and the detoxification of harmful substances in the body.

However, many host-associated microbes, including the gastric pathogen H. pylori, unexpectedly lack low molecular weight (LMW)-thiol biosynthetic pathways. H. pylori can acquire these thiols from the host environment using a highly selective process, giving them a survival advantage. Furthermore, Yale researchers found that human fecal bacteria metabolize ergothioneine, which may contribute to the production of the disease-associated metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide. Collectively, our findings illustrate a previously unappreciated mechanism of microbial redox regulation in the gut and suggest that inter-kingdom competition for dietary EGT may broadly impact human health – including stomach cancer.

* In the most basic sense, excess oxidation is a bad thing and can lead to a variety of diseases and accelerated aging. Increase Your Lifespan and Healthspan: A Comprehensive How To Guide